USING FALLEN TREES TO BUILD SOIL AND RETAIN WATER

FROM SOIL THEY CAME AND TO SOIL THEY SHALL RETURN:

HOW TO CYCLE FALLEN TIMBER

We are going to take a deeper dive into Permaculture in future emails for folks who are still kind of new to the concept, but I gave a quick overview in the last email (now published on my website blog), and it is important that I start getting out the practical “what do I do with this storm damage” information ASAP.

If you want to read more about Permaculture, check out this page on my website, and also stay tuned. We’ll get there.

You will come to see that Permaculture thinking is very intuitive, so let’s just dive in to something that a lot of people are dealing with right now:

“WHAT TO DO WITH ALL THIS DOWNED TIMBER?”

In the immediate days after the storm, everyone grabbed their chainsaws and got to work clearing the roads and making their way through the trees.

Then the many thousands of linemen (God bless them all) swarmed into the area with their accompanying tree crews and cleared the stuff off the power lines.

Arborists and others helped people get the trees off the roof and cut up on the ground. Good work all around.

However all the wood that got cut and cleared MUST GO SOMEWHERE.

Right now, a lot of it is being taken to facilities to be pulped and likely returned to the land via mulch. But that’s a lot of gas, time, and labor for trucks to haul all that material twice.

Before those trucks pick it up from the side of the road, it sits there making the roads narrow from the hazards on the roadsides. Before it gets to the side of the road, someone has to cut and haul and stack it there. In my opinion that is a lot of waste that yields no benefit at best and is extractive and detrimental to the environment at worst.

One of the principles of Permaculture is to “Produce no Waste.” It’s an acknowledgement that you can’t throw anything “away.” There is no such place as “away.” Waste must be put SOMEWHERE.

A forest is incredible at cycling its “waste” back into the system. We have much to learn from forests in this regard.

Think about the mass of a tree – where does the substance of a tree come from? Giant trees that are many stories tall and weigh many tons are made of the very same atoms that make up the soil -- the nitrogen and carbon and potassium and all those elemental building blocks of life. Even the water molecules that the trees uptake are broken down to their constituent parts. Even subatomically, the plant cells use the electrons from H2O to create glucose from carbon dioxide. O2 (the oxygen we breathe - thanks trees!) is a byproduct as well as hydrogen ions.

Trees are made of the soil they grow in. Trees ARE the soil they grow in, just reassembled into a structure, a living organism called a “tree.” (That idea could also lead us to ponder about what we humans truly are, but that is definitely another topic for another day.)

My point is this: all the leaves and limbs and trunks and roots of eons past are not piled up forever. They become the soil again.

They become habitat and food for the microbes, fungi, and insects at the base of the food chain and the birds that the forest uses to disperse its seeds. Their death is the rebirth of the forest. The become trees again. They become birds and bears and blueberries. They become part of us when we eat the food of the forest.

As long as that biomass remains in the ecosystem, that is.

We are clever creatures. We can see the big picture and understand that. We can also choose not to act accordingly.

I would like to propose a few uses for the fallen timber that are a bit more clever than just “let them rot where they lie” (though that is preferable to hauling them off in my opinion).

I realize that it isn’t feasible to leave huge brush piles in dense urban settings, but my guiding principle when dealing with downed timber is to try to reincorporate that biomass into the local soil as rapidly as possible.

We know what makes wood decompose, right? Dampness in which fungus can thrive is the most critical component.

Also, smaller pieces of wood will decompose faster than larger pieces.

So let’s try to create an environment where we can help nature to facilitate this process.

We can also use a permaculture tactic of “Stacking Functions” while we do this. Since we want to trap water to help decompose the wood, we will be trapping water. And when we trap water, we also slow down surface erosion and create more soil fertility by recharging groundwater.

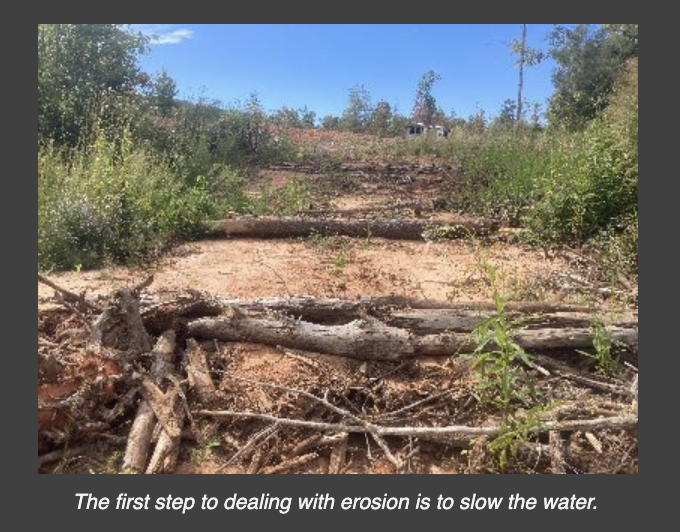

The first step to dealing with erosion is to slow the water.

HOW TO USE FALLEN TREES TO:

• PREVENT EROSION

• CREATE SOIL

• RETAIN WATER

1. BRUSH ON CONTOUR

Cut all the timber into manageable pieces and drag into a line/pile that is level across the slope. When looking at a topographical map, you would essentially be laying all the brush along a contour line.

What’s a contour line?

Quick topo map primer: Take a look at a map of my land. Those brown lines convey 3D information on a 2D surface. If you were to walk along one of those lines, you will not gain or lose any elevation. That line is the same elevation along its entire length. If you were to walk perpendicular to the lines, you will gain or lose 20’ of elevation with each line your cross. The closer the lines, the steeper the slope. More space between the lines means a more gradual slope.

So how do we read that map?

It is a sunny, generally south facing, relatively steep slope ranging from about 2500 to 2800 feet or so. Because of this dry, sunny, hot, steep slope, capturing as much water as possible is crucial for the fertility of my forest.

For the last 6 years, as I clear trails, remove invasive vines, and move the forest through its post-logging succession, I pile my brush on contour. Here is a quick sketch of just some of the places where I have brush on contour in my woods:

You can see the general idea here — just pile the brush in long level piles across the land.

This isn’t a strictly mathematical process. You don’t even really need to understand how to read a topo map. Much of it depends on how far you are willing to drag the wood. I would recommend starting at the bottom of the hill and working your way up. When it starts to feel like you are dragging brush too far, start a new berm. Maybe 15-20’ is the closest I would normally space 2 berms.

Hard to see in these photos, but these are four examples of brush on contour berms in various stages of decomposition on my land. I add to these year after year.

The beauty of doing this at this time of year is that you can utilize the fallen leaves more efficiently.

These berms will hold the leaves, speeding the decomposition of both. You can also cover the berms in leaves to occlude sunlight which slows evaporation and also discourages plants growing through the berms.

In a year, a berm will become one homogenous form - you won’t be able to pull it apart.

In 2-3 years, they start to disappear into soil, but the soil won’t wash away.

Because you placed it so carefully, the soil will continue to trap water long after the wood has decomposed. You have made a permanent change to the topography of the land (that’s the “perma” part of permaculture).

In time, the berms disappear, but the improved topography remains.

Also in the meantime, while it still is a pile of sticks, you will have created a ton of habitat for small mammals which are the basis of the diet of every Appalachian predator.

More habitat, more food at the bottom of the food chain, more life all the way to the top.

Likewise, most of our beloved birds are omnivorous and a significant portion of their diet is insects and other similar invertebrates.

And not to mention, fallen leaves are where lightning bugs lay their eggs so if for no other reason, leave the leaves so you can have more magical summer nights.

Best Practices For Doing Brush on Contour:

Mark your contour lines before you start stacking. It helps to either flag a line or layout a single line of sticks to get started. That way you can focus on getting it level to start, but once you start moving wood in earnest you can just focus on the physical aspects of the work.

You can pound vertical braces into the hill to hold logs to keep them from rolling as you get the berm established. By the time those vertical sticks decompose, the mycelia and general decay of the wood will keep it in place.

Start at the bottom and work your way up the hill. It is much easier to roll and throw the wood down to the berm you are working on than trying to carry things uphill. Once it feels like you are dragging things too far down to add them to the berm, start another one further up the hill.

Think of decomposition like the digestion process of the forest. The “food” is easier “digest” if it is “well-chewed.” This means the more you cut the wood, the more easily it will decompose. Try to cut the branches so they are more or less “poles” that can lay easily together in a dense, tight pile.

Try to keep it pretty “neat and tidy.” It shows intentionality when it is obviously constructed with a purpose.

Isn't it a fire hazard to pile up brush in my forest?

This may be counter intuitive, but creating long, tidy, brush contours is actually helpful in preventing fires. By piling the brush together, on contour, with the intention of trapping water, the goal is to keep the wood damp and in contact with the forest floor. Cleaning up" the forest and concentrating the brush in small, low, long piles reduces the chances of fires spreading through a landscape that has fuel evenly dispersed throghout it. The spaces between the brush berms make good fire breaks, especially if the leaves above the brush are raked onto the berms, exposing the soil above to allow plants to emerge and have access to sun.

And fire can be hugely beneficial if used the way nature uses it in forest ecosystems. See section on burning below.

2. CHIPPING AND “CHEWING”

If you have access to a chipper, by all means use it. Turning wood into wood chips is one of the best ways to speed the decomposition of wood. The more we chew our food, the easier it is to digest, right?

One option for the chips is to leave them to decompose in a large pile (bonus points for inoculating the wood with edible mushrooms). Then, using the resulting compost as a top dressing for gardens, orchards, or forests. This takes a year or two. The other option is to spread the chips into the forest, along garden pathways, etc.

One word of caution – Keep the wood chips ON TOP OF THE SOIL. Never bury wood chips. Wood is high in carbon and low in nitrogen. If wood is covered by soil, it will draw nitrogen from the soil to do its decomposition dance with the carbon in the wood. Plants grown in this soil will not have as much access to nitrogen, one of the main plant nutrients.

And this makes sense, right? A forest never buries leaves and trees under the soil. All the soil making magic happens at the soil horizon, right where the soil, insects, mycelium, oxygen, organic material (rotting wood, leaves, etc), and water can all work together to do their thing.

Likewise, if you do opt to keep your wood chips in a big pile, and you want to make them decompose even faster, you can add nitrogen to the piles. The most convenient source of high nitrogen “waste” is … buckle up … human urine. Gross, I know.

But our society concentrates all that nitrogen into our sewers and wastewater treatment facilities where it cannot be reclaimed by earth in the way that it has been cycled through all of time – in soil. So yeah, kind of extreme, but I have a few mentors who make compost this way. I won’t go into any more detail on that, but there you go. Message me if you want more details.

3. BURNING - DON’T DO IT! (AND A FEW CAUTIOUS CAVEATS)

This is many people’s strategy for dealing with waste wood. And while there is a place for this if applied responsibly and correctly, I actively discourage open burning in nearly all contexts.

Harvesting oak and locust for wood stove fuel is always a good idea. However, I wouldn’t let someone come out and take all my wood away to sell it later. I wouldn’t let them come with a dump truck and haul away my topsoil either. Harvest enough for your needs for a few seasons, but once it starts getting soft, turn it into soil.

Here is why I discourage burning in the immediate aftermath of the storm:

Trees, leaves, and limbs are still full of moisture many months after tissue death. Burning “green” wood requires a lot of fuel and creates a lot of smoke.

People are already under stress and the smell of wood smoke in the air will adds more stress. We have a deep, evolutionary relationship with woodsmoke. The smell of lots of green wood smoke creates parasympathetic responses in our nervous systems, not to mention the local fauna.

It hinders the ability of emergency responders to see real emergencies

Forest fires caused by downed power lines

Structure fires caused by unsafe cooking and heating practices due to power outages

Fires in remote areas can be signals of where to look for people

People with respiratory ailments do not have access to medications, inhalers, or power to run CPAP machines and other medical equipment.

Fires can get out of control and require resources from emergency services that are already stretched thin.

And, it does not help stabilize slopes. It only sends into the atmosphere all the matter that could have been reassembled into soil

CAVEAT 1: BIOCHAR IS A PERMANENT SOIL AMENDMENT

However, there is a great way to control the combustion of wood to create charcoal that can be biologically “activated” with organic materials to permanently improve soil fertility. This product is called “Biochar.”

I will not go into the specifics of how to make it or why it is so great for soil and plants right now. Great information on the topic is readily available on the internet from sources with more experience than I have.

Here is a quick overview to explain the concept of Biochar: wood is burned, but not completely. This is achieved by creating an environment where the wood is exposed to high heat, but not to oxygen, in a process called pyrolysis. This creates a different chemical reaction resulting in charcoal instead of ash, the product of complete combustion.

Charcoal is essentially pure carbon that is extremely porous at a microscopic level. Once cooled, this charcoal can be steeped in nutrient rich slurries, mixed into compost, or inoculated with microbial or mycelial solutions. The pores hold the nutrients and create excellent habitat for all these beneficial microbes while also adding more capacity for water retention to the soil.

source

Biochar under a microscope. This is incredible habitat for an ecosystem of beneficial microbes as well as tiny sponges for water retention. Permaculture is all about creating environments to nurture the flourishing of life at all levels

The crushed biochar can be mixed into compost, applied as a top dressing to gardens, or simply dispersed into the forest.

Again, there are many excellent how-to guides online about different methods for creating the pyrolysis environment with simple and cheap every-day type hardware store items. This is definitely something that you will need to do more research on, and you will never be able to make biochar at a scale big enough to use whole trees. I have only done a bit of this on my land, so I am no expert, but it certainly does have its applications. Again send me a message if you want to discuss this further.

Igniting a controlled burn. Notice how the burner is on the downwind side of the area to be burned, walking in a "firebreak" that has been cleared of combustible material. As the fire spreads upwind slowly, the wind will only blow the fire toward areas that have already been burned. Firebreaks and wind direction are the main ways fires are controlled.

CAVEAT 2: PLANNED BURNS ARE NATURAL AND BENEFICIAL

Fire is a natural part of our local bioregion. The perpetual suppression of fire has negative impact on the ecosystem. The decomposition of leaves and limbs is the normal seasonal cycle of the forest, but many species depend on occasional fire to move through the area and reduce the forest floor to the mineral soil. This is what creates a "Grassland Savanna" ecosystem, which is what much of our forests would have looked like before human intervention.

This is the same forest (note the circled tree) after a burn, creating an Oak Savanna ecosystem (left) and the closed canopy forest before (right). Think about which type of forest you see more often. 500 years ago, the savanna would have been far more common.

When fire moves through the forest floor, it generally burns hot and quickly, leaving the mature trees, but scorching everything else on the forest floor (first photo below).

(Don't worry, the critters have co-evolved with fire and they will clear the area and return almost immediately to the improved conditions.)

When the duff and saplings are reduced, the soil is now open for the emergence of flowers and grasses that have evolved to take advantage of this window to out compete the trees. An abundance of light can reach the forest floor and the flowers and grasses thrive. This is the habitat for native quail and turkeys. The decline of quail populations are directly correlated to the reduction of fire in the ecosystem - most of us have never heard a bobwhite's song. Small mammals thrive on the roots of the grasses and flowers and the cover they provide. Then too do their predators thrive, especially the aerial predators who now have clear line of sight and flight paths through the open woodlands.

Periodic fires also protect the forests from larger, more devastating "canopy fires." When the forest floor reduced to mineral soil occasionally, it doesn't have the chance to build up huge amounts of fuel that create extremely hot fires that can enter the canopy layer and destroy entire forests (second photo below).

If you are interested in pursuing this option for forest management, I am definitely an advocate for the practice and I would like to help you make a plan for that. In North Carolina, there is a law called the Prescribed Burning Act to guide landowners on this practice. There are "Certified Burners" through the NCFS that will create prescription and burn plan before the fires are conducted. I will have a newsletter specifically on this topic later, but in the meantime start here at the NC Forest Service website, and/or watch this video, and/or read this handbook and/or contact me and we can work together to make a plan to revitalize your woodland with fire together.

CONCLUSION

Who knew there was so much to talk about regarding rotting wood? Thanks for sticking around to the end.

The main idea here is to USE THE WOOD WHERE IT IS, to physically retain water and soil now and into the future as it decomposes. Use the wood to slow the downhill velocity of surface water, spread the water across the contour, and sink it into the soil. And you don’t have to drag the wood as far. Win-win-win.

I do this all the time in all kinds of crazy terrain. If you prefer more hand-on learning, I’d love to come over and help you for a half-day or so and teach you how this is done. I’ll suit up and bring my saws, loppers, contour marking tools, etc. and we can work together to get your brush on contour berms started. We can get a whole lot done if you muster up a group of friends willing to come over and help. You, me, and a half dozen of your hard-working friends can do a lot in a few hours.

Get in touch if you have any questions or want to talk about your particular site. I'm here to help you help your land.

Yours in unity in the Web of Life,

Luke "Gribley" Costlow